David Shanet Clark, M.Ed. Online Journal ... scribners.org

|

|

|

|

|

Seceding from Secession:

Geographic Factors in the

Political History of West Virginia

By David Shanet Clark

Upland West Virginia, with her contemporary and fantastic Appalachian

Mountain region forest vistas, wild and wonderful Dolly Sods' area own surrealistic vegetation, her unusual Blackwater Falls

and Seneca Rock Allegheny topographic regions, with her native Black Bear, Bobcat, Beaver and Fox wildlife habitat populations;

her Shenandoah, Greenbrier and Potomac River colonial refuges, all these aspects show that West Virginia is today a living

relic of the great colonial, federal and victorian eras' American frontier region. Along the high Allegheny ridgeline

some rare old growth forests stand as they did six, eight, ten generations ago, a formidable force.

Many

of the rural people still resist the encroachments of modernity and urbanization. West Virginia’s annals of geographic

and geologic history, the study of Greater Virginia geography since the seventeenth century, reveal to us the importance of

the Allegheny Mountain Ridge to American history. The history of West Virginia has been examined by capable writers, and

the nineteenth century view of the new State stressed the theme of loyal citizens, showing loyalty to the Union. Western

Virginia occupied the center of the national demographic map for the first decades of the nineteenth century, and it was a

central part of the American frontier from the 1700s through the late antebellum era.

The most contested U.S. domestic

issue in early nineteenth century was the internal improvements debate. In 1817 President James Madison found Federal investment

in post and military roads to be constitutional. The National Road that Congress chartered stretched from Cumberland,

Maryland to the Ohio River and passed through present-day West Virginia. This extension of the settlers’ westbound Potomac

River route formed a strategic and developmental mainway from the Federal capital city inland to the Ohio River System, the

Old Northwest Territory and the Mississippi Valley.

Forty-five years later, when West Virginia seceded from Confederate

Virginia to join the Union, the Federal government gained the strategic defense of the National Road, the 1853 Baltimore and

Ohio Railroad along a parallel route, the Potomac River itself and the western Shenandoah waters at the west of the Allegheny

Ridge. With West Virginia, the Union firmed up the Ohio, Maryland and Kentucky area’s strategic security -- and helped

clear the Ohio River from Pittsburg to Kentucky.

The Ohio River linked the Union and West Virginia completed the

bloc of loyal Border States. Students of geopolitics should familiarize themselves with the High Allegheny continental watershed

and the relationship of this massif to events in Native American, French, and British eighteenth century history -- as well

as to the nineteenth century Union vs. Confederacy strategic realities. George Washington knew the crucial importance of

the old Virginia frontier, in 1785 the Potomac Company incorporated to build a canal to connect the Potomac River with the

Cheat River and the James River Company was incorporated to construct a canal to connect the James River with the Great Kanawha.

George Washington was made President of both chartered groups. The National Road was completed from Cumberland, Md. to

Wheeling, Va. in 1818, while the first commercial steamboat on the Ohio River dates to 1817. The Staunton to Parkersburg road

from the Great Valley to the Ohio River was established between 1823-1847. The Winchester to Parkersburg Road was completed

in the 1830s. With settlements established, almost all after 1790, by Germans, Scots, Irish and various pioneers who had migrated

southwest from Baltimore, Philadelphia or New England, western Virginia had little of the Anglican tobacco plantation interests.

Good roads pushed through the interior hollows in the Clay-Jackson period and they developed and improved the economy.

It is significant that the United States Census of 1820, 1830, 1840 and 1850 show the center of U.S. population moving west

over time -- across present day West Virginia, like a slow wagon of popular political weight moving west out of the old colonial

Atlantic area into the Ohio Valley and by 1860 into Ohio and the old northwest territories. The completion of the Baltimore

and Ohio Railway in the winter of 1852-1853 brought a quickening of market prosperity for the mixed agricultural families

-- now less dependent on game. As hard pioneer conditions abated in much of western Virginia, due to steam-powered river

transport, wood and coal fired railroads, new roads and bridges, then the region’s cultural and political establishment

reached new heights.

West Virginia was both made and unmade by the war. The New River, the Kanawha River

and other rivers in the Ohio-Mississippi-Gulf system; the Cheat River, the Guyandotte, the Elk River, the Gauley River and

the Greenbrier River are all interesting for their effects on important trade, development and political boundary decisions.

When Virginia seceded from the Union and joined the Confederacy in 1861, the people of these western river valleys mobilized

immediately for resistance and Union statehood. Western Virginia political leaders were recognized by the Lincoln Administration,

and sat in the wartime House and Senate as loyalists, or Reformed Virginia representatives. By 1863 a series of conventions

and lop-sided elections had established the new state, West Virginia.

Marked by its sprawling, irregular shape

and mountainous terrain, West Virginia is poorly understood by many 19th century and civil war historians, probably because

no great armies ever fought there. Strategically, however, the severance of the Northwest half of Virginia had great impact

on the Confederacy -- and the Union. This minor general theater of campaign, West Virginia, had one major railroad, the Baltimore

and Ohio, and the river systems mentioned above. As John Shaffer states: "Federal success in Western Virginia

gave the north its most important victory of the first year of the war. A third of Virginia had been won to the Union, territory

from which its Armies could be launched deep into the Confederacy. In the spring of 1862 the U.S. high command launched a

2-pronged attack into the Shenandoah Valley from Western Virginia." A few battles and countless skirmishes by Gen.

McClellan cemented the new border, which carefully followed the high ridge of the Allegheny Mountains, and for many miles

the border shares its identity with the actual watershed between the Ohio River or Mississippi Gulf-bound tributary waters

-- and the Chesapeake Bay / James River and Atlantic Ocean bound mountain headwaters. Here in the less populated cold

and rugged hinterlands, both the Union and the Confederacy could tacitly utilize the high defensive wall of the Allegheny

Ridge to their mutual tactical and strategic advantage, or stalemate. The Union gained the Ohio River system, the Potomac

River, the route of the old National Road and the 1853 Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, the northern panhandle of old Virginia

near Pittsburg, plus Harpers’ Ferry (strategic river/rail confluence) and the old buffalo cattle trail road across the

mountains from Lewisburg to the Kanawha and Ohio Valleys, the Midland Trail.

By November 1863 U.S.A. General William

A. Averell defeated the Confederates at Droop Mountain and ended rebel control of the Greenbrier River Valley. This “produced

a considerable degree of congruity between territory within the boundaries of the new state of West Virginia and that actually

under the control of its authorities.”

The Old National Road through Cumberland, Maryland

to the Ohio Valley by-passed western Virginia and propelled settlers to points west, north and south of the trans-Allegheny

Virginia hinterland region. This is the central historic impact of the Allegheny High Ridge on U.S. history in the antebellum

and colonial contact periods. Indeed, there were trails and a cattle road into the trans-Allegheny, or today’s West

Virginia. The Native American Midland Trail linked Staunton, in Augusta County Virginia in the southern Shenandoah Valley,

with the Greenbrier and Kanawha River systems in West Virginia. Between the Blue Ridge Valley and the farmland near Kanawha

Falls lay nearly impenetrable ravines, forested escarpments, the New River Gorge -- and the wildest Gauley River rapids. Only

animal trails, widened by cattle traders, carried frontier farmers through the southeast section of today’s West Virginia,

until road building began in earnest in the 1830’s and 1840’s. Another rugged 19th century road led from Monterey

to Beverly, but these were little more than trails until circa 1830. George Washington recognized the importance of linking

the settled parts of Virginia to the Ohio Valley in the late eighteenth century, “I aver, most seriously, that I wd

not give my tract of 10,990 acres on the Kanawha for 50,000 acres back of it, and adjoining thereto, nor for any 50,000 acres

of the common land of the country, which I have seen, back from the water and in one body.” Washington understood his

river bottoms to be “Extremely valuable” and worth five times the inland tracts. Washington stated that common

western Virginia land values in the Adams administration to be “half a dollar or less per acre.” Washington also

owned large tracts of land in the Great Bend of the Ohio River -- and his family was prominent in the Harpers Ferry and Berkeley

Springs part of what later would become West Virginia. With the completion of the National Road, then the James and Kanawha

Turnpike and finally the Staunton to Parkersburg Road the ‘west’ was settled -- but a series of constitutional

conventions show that the western denizens of Virginia held bitter feelings for the Richmond government long before the Confederacy

crisis of 1861. Poll taxes discriminated against the low income Westerners and the tax on property included a bias in favor

of slave-holding interests. With state government offices and banks centered in Richmond the people of the West felt the sting

of poor government services and high travel expenses, on top of tax and representation imbalances. The high remote hinterlands,

a band of counties along and in the Allegheny highlands, sharply divided political opinion in the period before secession.

In the wartime partition of Virginia into Union and Confederate halves, a constitutional contract formed between the Union

government and the political leadership of the Trans-Allegheny region. The contract extended to an area that the West Virginians

could lead into statehood against the Old Dominion’s Richmond government. The Union negotiated with the seceding anti-secessionists,

who conducted overwhelming polls against Richmond. With the results in hand, they Wheeling Union loyalists met with an enthusiastic

reception in wartime Washington. Benjamin Wade squired a Statehood Bill through the House, and Cabinet members William Seward,

Salmon Chase and Edwin Stanton advised Lincoln to sign it. Francis Pierpont, Governor of Reformed Virginia and U.S. Senator

Waitman T. Willey were West Virginia’s native founders. Union arms had secured the bulk of the state to the Union militarily,

and by June 23, 1863 the new State had full status in the Federal Union.

(continued below)

|

| | | The Oldest House in West Virginia 1743

Gerrardstown W.Va.

|

|

|

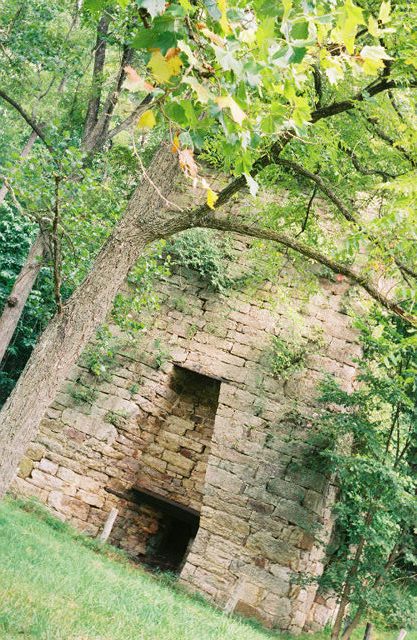

Photo - Iron Furnace

Shenandoah

Valley

West Virginia 1844

35mm 1959 Agfa 2004

Photo by Shanet Clark

(Text

-- continued)

The Trans-Allegheny region was joined to a secure corridor of eastern counties and a

smaller northbound salient. The Eastern Panhandle of the new state secured the Potomac River and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad,

while the Northern Panhandle protected the industrialized ironworks at Wheeling and the Union’s southbound Ohio River.

So both the eastern and northern irregularities are explained.

The 20th century French historians Fernand Braudel and Marc Bloch understood

that long duration geographic factors might in some ways dominate human industry, culture and political behavior. George Washington,

Peter Jefferson and Thomas Jefferson were cartographic surveyors, and the history of the colonial and federal (eastern) frontier

is one of land claims and jurisdictional issues in which accurate knowledge of space, terrain and remote topography were of

central importance. Human agency is restrained by physical factors in the environment. Floating down a river is easy, but

climbing over a mountain is much more difficult. Braudel’s theory of la longue duree is a good approach to the history

of the trans-Allegheny region. Time passes in different cycles in the rural mountains, between rural small towns and the coal

and chemical producing cities, and geologic destiners drive political events. The event horizons of recent history are formed

by a longer pattern, the Olympian view of the old frontier can show high mountain ridges and their swift river systems impacting

history -- and dividing colonial and Federal era frontier people more or less neatly. Human agency is determined in some degree

by forbidding or compelling geographic realities. The importance of the watershed over the long term cannot be underestimated.

The Shawnee and the Cherokee are known to have used the border states of Kentucky and West Virginia as a buffer zone in the

first contact period. Happy Hunting Land was here. When the Proclamation Line of 1763 was promulgated by George III to end

westward frontier expansion into the freshly conquered French northwest territories, the line followed the high ridge of the

Alleghenies, from the southwest to the northeast, incorporating nearly the present border of West Virginia and Virginia. The

Southern Methodists’ break from the Northern Methodists in 1844 also followed this line. The French, following LaSalle’s

expedition, laid claim to the Ohio tributaries from the River to the highest sources, i.e. the French claimed the west Virginia

part of old Virginia in the 18th century until 1763. One of the oldest and most simple maps of this region labels West Virginia

and Kentucky simply as Florida, showing a primitive Spanish claim. French, English and Spanish border conflicts were quite

fluid in the 17th and 18th centuries. The Ohio River is a very plain demarcation, but the high ridge is less manifest to the

eye. Confronting the Allegheny massif, a forbidding front broken by gaps, western explorers were steered around present day

West Virginia. The Warrior Road became the Great (Shenandoah) Valley Road and it trailed off to the southwest to pass through

the Cumberland Gap as the Wilderness Road to the Bluegrass; here Simon Kenton and Daniel Boone carved a route that led rustic

Virginians out of old Virginia, and into the Ohio Valley. The Shenandoah Valley, with its slaves enduring General Stonewall

Jackson’s campaign theater, was not enrolled in the new state in 1863; the Valley, east of the high Allegheny watershed

ridge, but west of the mighty Blue Ridge, remained within the Confederacy and the Old Dominion, within its geographic and

Atlantic-bound rivers’ region. Just as the southwesterly Wilderness Trail through the Cumberland Gap the Allegheny massif

propelled all but the hardiest explorers and frontier families to go north, through Cumberland, Maryland and then north to

Pittsburgh, where the mighty Ohio River carried them south and west through the Ohio Valley, again bypassing western Virginia

-- unless they disembarked on the left bank before reaching Kentucky... The Cumberland Gap and Wilderness Road route worked

in the other direction as well. During the Lewis and Clark expedition an envoy of Osage Indians led by Peter Choteau went

“eastward from St. Louis to Vincennes, Louisville, Frankfort, Lexington, through the Cumberland Gap and then [north]

down the Shenandoah to Winchester, and on to Shepherdstown, Maryland, Harpers Ferry and Frederick [Md.] to Washington.”

The Potomac River was the original corridor into the ‘west,’ and by 1818 the National Road ran from Baltimore

along the Potomac to Cumberland, Maryland and on to Wheeling on the Ohio -- in present day West Virginia. The Baltimore and

Ohio Railroad reached the same spot by 1853, along a similar route.

The B&O Railroad and the National Road

are seen as wartime strategic corridors, essential to the Union’s transportation needs. The Ohio River, the Potomac

River and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad were all secured by the new arrangement of loyal and confederate counties in old

Virginia.

Marked by a few high mountain gaps, the new border formed a defensive wall, amenable to the south, and formed

a defensive wall for the Union forces in West Virginia, as well. As a strategic conquest, the West Virginia 'counter-secession'

must rank with C.S.A. General Joseph E. Johnson’s precipitous retreat from northern Virginia as an early strategic transfer.

Numerous historians have noted that the fate of the border states decided the war, and this new border state of

West Virginia marked a significant strategic conquest on the part of the Union, as the State secured the Ohio River, its Virginia

tributaries, the iron works at Wheeling, much of the Potomac River system and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

Vulnerable

bridges and towns along the B&O were raided and West Virginia towns such as Martinsburg and Romney; and Harpers Ferry

changed hands repeatedly, but the borders held to the Union’s advantage as the fighting came to center more on points

south after the battle of Gettysburg.

When the highest Ridges were linked to encompass the Ohio River waters into

the new state, this political boundary line marked the watershed of Atlantic versus Gulf runoffs --- south of the line rainwater

runs through the Greater James and Rappahannock systems, while north of the line, the New River and the Kanawha waters rolled

down the Ohio to the Mississippi and the Gulf of Mexico.

Thus, the politically stable Atlantic Northeast was joined

to massive inland ‘western’ power. The Northeast and Old Northwest Territory states enrolled the south bank of

the Ohio (West Virginia and Kentucky) into its Union and Republican government.

I find it very interesting that radically

dissenting political forces, in the heat of an unprecedented civil war, decided upon the watershed at the high Allegheny dividing

ridge to be the ultimate extent of the new Union state. County by county, the Union power was strongest along the Ohio River

and was contested more convincingly inland. The new state’s founders rejected counties lying now in Virginia, the tiers

of counties along the border and the Shenandoah Valley. The founders knew that secession interest was stronger in these counties

-- closer to Richmond -- and the number of slaves and free blacks in these Great Valley counties were also at issue.

Waitman

T. Willey and the other founders limited the state to western Virginia counties with strong white majorities. Lincoln’s

government sent the State bill back to the convention and demanded an emancipation clause in the new West Virginia Constitution,

which was added before the final vote which led to Lincoln’s signature in June 1863.

Ultimately, geography

determines political junctures because of strategic imperatives inherent in the topography. By late 1862 the Union did in

fact lay military claim to the high ridge of the Alleghenies, and the differences in settlement patterns, labor and crop approaches,

informed by the terrain, reached their conclusion in the new State. As Dr. Shaffer shows clearly, the west Virginians of 1861-1863

who joined the Confederacy as individuals had a high proportion of Virginia native parents and grandparents, while Unionists

had more Pennsylvania, Maryland and Northeast born ancestors. The unique shape of West Virginia, its geometrically irregular

and sprawling non-compact form actually follows from common sense geographic principles. Strategically the new State aided

the Union by: securing the defense of Washington D.C. and the Potomac River; in the defense of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad,

the National Road and the Chesapeake and Ohio canals along the old Virginia-Maryland border; cleared the Ohio from North of

Pittsburg to South Point Ohio, firmed up Southern Ohio and Southern Pennsylvania’s situation relative to Maryland and

Kentucky, the true border states, and this meant the loss of Weirton and the Pittsburg area north Virginia salient to the

Confederacy. The southern border provided a wall of defense. The three concepts of rivers, high watersheds and strategic corridors

can explain the panhandles and ‘teapot’ shape of W.VA. Armed with geographic, climate, elevation, rail, road and

river topographic facts, the political and social events leading up to counter-secession and West Virginia statehood can be

understood.

Works

Cited:

Ambler, Charles Henry.

Sectionalism in Virginia from 1776-1881. Chicago: University of

Chicago Press, 1910.

Ambler, Charles Henry.

West Virginia, The Mountain State, Chicago: University of Chicago

Press, 1958.

Anderson, Fred.

Crucible of War: The Seven Years War and the Fate of Empire In British North

America. New York: Publisher, 2000.

Barraclough, Geoffrey.

The Atlas of World History.

New York:

Harper Collins, 2001.

Blow, Michael.

History of the Thirteen Colonies.

New York: Simon and Schuster,

1967.

Braudel, Fernand.

Memory and the Mediterranean.

Callahan, James Morton.

History of

West Virginia:

Old and New.

Chicago: 1923.

Colton, Calvin.

The Private Correspondence

of

Henry Clay.

Boston: Frederick Parker, 1856.

Craf, John A.

Economic Development

Of The United

States.

New York: McGraw Hill, 1952.

Crofts, Daniel.

Reluctant Confederates:

Upper

South Unionists in the

Secession Crisis.

Chapel Hill UNC 1989.

Faulkner, Harold.

American Economic

History 8th Edition. New York: Harper and Row, 1960.

Geiger, Joseph.

Correpondence.

Guyandotte,

W.Va.

(grave monuments' texts)

Hall, Granville D.

The Rending of Virginia. Chicago: 1901.

Hogan, Roseann R.

“Buffaloes in the Corn: James Wade’s Account of Pioneer Kentucky” The Register

of The Kentucky Historical Society. Vol. 89, #1 Winter 1991.

Holmberg, James, ed.

Dear Brother: Letters

of William Clark to Jonathan Clark.

New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002.

Hull, Forrest.

A Forrest

Hull Sampler. Richwood W.Va.: Jim Comstock 1960.

Martineau, Harriet. Society in America London.

London:

Saunders and Otley, 1837.

McCardell, John.

The Idea of a Southern Nation: Southern Nationalists and Southern

Nationalism 1830-1860.

New York: W.W. Norton, 1979.

Rice, Otis.

A West Virginia History.

Lexington:

University of Kentucky Press, 1980.

Shaffer, John.

Clash of Loyalties:

A Border County In the

Civil War. Morgantown: WVU Press, 2003.

Stealey, John E.

The Antebellum Kanawha Salt Business and Western

Markets.

Lexington, Ky.: University Press of Kentucky, 1993.

Stephenson, Richard W.

and Marianne

M. McKee.

Virginia In Maps:

Four Centuries of Settlement,

Growth and Development. Richmond: Library of Virginia,

2000.

Twohig, Dorothy, ed.

Letters of George Washington, Retirement Series. Charlottesville: UVA Press,

1998.

Von Glahn, Richard and

Paul Jakov Smith, eds.

The Song Yuan Ming Transition in Chinese History:

Imagining Pre-Modern China. Cambridge:

Harvard University Press, 2003.

West Virginia, Atlas and Gazetteer:

Detailed Topographic Maps. New York: DeLorme, 2001.

Willcox, Cornelius DeWitt.

A French English Military

Technical Dictionary. Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1917.

Writers’ Program of the Works

Projects Administration.

West Virginia:

A Guide to the Mountain State. Washington:

WPA and Oxford University

Press, 1941.

Georgia State University; Atlanta, Ga. |

|

The

Shenandoah Valley

Berkeley County West Virginia

35mm 1959 Agfa 2002

Photo

By Shanet Clark

"The politically stable Atlantic Northeast had joined with the massive inland power of the

Mississippi and Ohio. And this process occurred because of continental, geographic factors of long duration. Braudel's Long

Duree of geographic reality played out as strategic political reality in the case of West Virginia."

|

|

|

1740 Hayes House Top View

Gerrardstown,

West Virginia

35mm 1959 Agfa 2004

Photo by Shanet Clark

|

|

“Seceding From Secession,

Strategic and Geographic Factors

in West Virginia History.”

The Conference Lecture: UGA, GSU, Va. Tech, the OAH, FCA and at the New England Historical Association.

By David Shanet Clark

DeKalb County Historic Preservation Commission Chairman

"We will be considering the wartime partition of Virginia in 1863. The Western

counties of Virginia had harbored resentments against the Richmond government since before the Revolution. The “no-settlers”

Line of 1763 had roughly followed the present boundary, which left the west Virginians with no political or military support

along the frontier. In the Federal era West Virginia grew slowly, with few slave-owners settling in the forested hollows beyond

the Allegheny Ridge. With the three-fifths clause giving representation to 60% of Virginia’s slaves in Congress, the

sparsely settled interior counties were restive, and efforts at political separation were begun in the 1820’s. Resentment

over the distances the westerners had to travel to get to Richmond was costly and a feeling of second-class participation

in the distribution of services was building up west of the Alleghenies. When the civil war started and Virginia joined the

confederacy in 1861, there was strong support for separation in the western counties. Twelve hundred civic leaders met in

Clarksburg, then Wheeling became the center of the effort, and a state wide referendum led to recognition of statehood in

June 1863. In the late 1800’s the capitol was moved from Wheeling to Charleston, near the center of the new state. The

West Virginia statehood process can be seen as a contract between the leadership of the Trans-Allegheny Virginia counties

and the federal government of Abraham Lincoln. The two parties negotiated secession from the confederacy, secession from secession,

and this wartime process has some obvious strategic aspects, based on the unique geography of West Virginia. Two majors routes

west had been available to settlers in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The Wilderness Road, also known as the Great

Wagon Road, ran southwest from Winchester to Roanoke, then nearly due west to the Cumberland Gap, where Kentucky, Virginia

and Tennessee meet. This is the route of Daniel Boone’s group, Virginians who settled in the bluegrass farm country

of Kentucky. The Wilderness or Great Valley road ran along the Shenandoah River, (which flows north to the Potomac) through

the famous Valley of Virginia. The “Valley” lies between the Blue Ridge and the Allegheny Mountains. The other

historical route west in these latitudes was the National Road, which ran closely parallel to the Potomac River. The Potomac

River is the border between Maryland and Virginia and it flows almost due east. The builders of the National Road and the

Baltimore followed the Potomac River and Ohio canal followed the national Road in the 1820’s. Settlers would follow

the national road west to the Ohio River, or turn north into Pennsylvania and take the Ohio River south from Pittsburgh into

Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana and Illinois territory. Whether following the Wilderness Road southwest in wagons or the national

road to the Ohio, the land-water route, settlers by-passed present day West Virginia because of its mountainous terrain. The

Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Company developed the national road route into a railroad in the 1840’s and 1850’s,

and by 1858 the B and O ran from Baltimore, through Harper’s Ferry, over the Allegheny Ridge, to the interior of Virginia,

and all the way to the Ohio River. Here West Virginia is invested in the strategic transportation routes of the Union. The

strategic corridor concept of military history explains the otherwise anomalous shape of West Virginia. The Eastern panhandle,

the 3 o’clock arm of the new state included the counties running along the Potomac, it essentially secured the Potomac,

the National Road, the B and O canals and the B and O railroad from Confederate interference. The northern panhandle, the

12 o’clock arm was a northern, industrialized area of Virginia, between Pittsburgh Pennsylvania and Steubenville Ohio,

and at the time, Wheeling was a leading industrial center. This area was greatly influenced by northern industrial and political

currents, and had little use for the slave economy based in Richmond. The northern panhandle, a true military salient, was

lost to the confederacy, and the Union gained a strategic corridor protecting the Ohio River and the westernmost lines of

the B and O. So we have two strategic corridors in the panhandles, one protecting the Potomac and the B and O, the other protecting

the Ohio, the B and O and the Wheeling Industrial area. Another strategic geographic factor in the partition was the forbidding

nature of the Allegheny Mountains. No railroad line at that time crossed the Alleghenies south of Harper’s Ferry, and

the high mountain ridges, running from the Southwest to the Northeast, had long divided the markets and political economies

of the two regions. With statehood the Allegheny ridge became a wall. The midland trail, through Lewisburg and Greenbrier

county was a traditional route, and farther north the Staunton Parkersburg road wound up into the high Appalachians, but these

two routes had no rails, and furthermore, General McClellan had secured the western towns early in the war, in actions between

Droop Mountain and Philippi. This wall secured W. Va. from confederate forces and Virginia from Union forces, and helped focus

the fighting in the Valley and the Piedmont, where there were railroads and enough open ground to deploy armies. The highest

ridges of the Alleghenies were the boundary because these ridges had formed the boundaries between the east facing and west

facing counties. The jagged edge is caused by straight lines connecting high ridges, but the WV-VA line follows the Allegheny

Ridge closely. The Richmond governments (of Virginia and the Confederate States) held on to the southwestern counties, which

gave them a strategic corridor into Tennessee and points south, and heavy fighting in the southwest allowed the South to secure

considerable Salt and Lead mines, this area was not lost to West Virginia. So now we can look at a theory of history even

grander than that of strategic corridors and mountain frontiers. The Long Duree, a concept made popular by the Annales School

of twentieth century historians, applies here. The Long Duree concept of history states that geologic time, and great geographic

constants, plays a role in human events. Britain, the Mediterranean and the eastern European steppes have all been illuminated

by the application of this theory, and I believe the significance of the partition of Virginia and West Virginia is best understood

via the Long Duree. The key word here is watershed. The geology of the rivers is causative forces in the history of the are

and perennial forces in human behavior there. Virginia was settled from the Chesapeake Bay, of course, and Virginians moved

inland along the James River, the York, the Rappahannock and the Potomac. These rivers carried Virginians through the tidewater,

up into the piedmont and the Valley. The headwaters of the James and Potomac are found high in the Alleghenies, along the

ridge. The rivers of Virginia flow into the Bay and into the Atlantic. To the west another social and political group emerged.

This group of people were beyond the Alleghenies, and their rivers led to the Ohio, the Mississippi and the Gulf of Mexico.

West Virginians drank from fresh water geologically separate from the Atlantic bound rivers of Virginia. In the western counties,

the Greenbrier River, New River, the Kanawha River and the little known Guyandot River flowed into the Gulf of Mexico. It

is no coincidence that the political, social and economic boundaries follow this timeless and geologic element. It is also

possible to apply this approach to the Union’s expansion at this time. With the Republican Union forces in possession

of everything north of the Potomac and Ohio rivers, the added political power of the southern Ohio Basin, Kentucky and West

Virginia was critical to strategic war interests. Not only was the North securing its industrial, rail and river interests

with the eastern panhandle and northern panhandle of the new state, by pushing forward (southeast from the Ohio, toward Richmond)

and securing the watershed of the Mississippi-Ohio all the way to the High Allegheny ridge, the Union was combined with the

old New England and Pennsylvania area states with the entire western watershed, and this isolated the south. The politically

stable Atlantic Northeast had joined with the massive inland power of the Mississippi and Ohio. And this process occurred

because of continental, geographic factors of long duration.Braudel's

Long Duree of geographic reality played out as strategic political reality in the case of West Virginia."

|

Victorian Iron Forge

35mm 1959 Agfa 2004

Photo By Shanet Clark

|

|

David Shanet Clark

Harpers

Ferry West Virginia

35mm 1959 Agfa 2002

Photo by Beverly Clark

|

MONTANI SEMPER LIBERI

SOURCES AND NOTES ON LEAD ARTICLE:

Harold Faulkner, American Economic History 8th Edition

(New York: Harper and Row, 1960), page 100; and John A Craf, Economic Development Of the United States (New York: McGraw Hill

1952), page 122. /

Anderson, Fred. Crucible of War: The Seven Years War and the Fate of Empire In British North

America. (New York: Publisher, 2000), Introduction, page 10.

Writers’ Program WPA West Virginia: A Guide

to the Mountain State, (Washington: Oxford University Press 1941), page 45.

Otis Rice, A West Virginia History

(Lexington, UK Press 1980), page 151. On February 18, 1862 the Convention approved West Virginia Constitution unanimously,

with subsequent election polls: 18,862 for, 514 against. The March 26, 1863 statewide vote: 28,321 for statehood, 572 against.

Among Union Soldiers: 7,828 for, 132 against. Significantly, Calhoun, Greenbrier, Logan, McDowell, Mercer, Pocahontas, Raleigh,

Webster and Wyoming Counties sent no returns—these counties were occupied or seriously disrupted by confederates and

“engrossed” into the new state by Unionist refugee representatives in Wheeling.

John Shaffer, Clash

of Loyalties: A Border County In the Civil War (Morgantown: WVU Press, 2003) quotes James Morton Callahan’s History

of W.Va. Old and New (Chicago, 1923) Vol. 1 p. 332, where Waitman T. Willey said: “West Virginia belonged, by nature,

not to Virginia, but to the valley of the Mississippi, its natural outlets were south and west with Cincinnati and Chicago

with Pittsburg in the North, with Baltimore in the East.” Shaffer also quotes Granville D. Hall, The Rending of Virginia

(Chicago, 1901): “Mountain barriers had been reared by nature between the two sections…commerce divides with

the watersheds and flows with the streams. The interests and purposes of men follow commercial lines.”

Shaffer,

Clash of Loyalties, page 83.

Rice, West Virginia, page 138. Also see Writers’ Program WPA West Virginia:

A Guide to the Mountain State, (Washington: Oxford University Press 1941), page 100, “A crooked line following the crests

of Dividing Ridge and the Allegheny Mountains for 365 Miles would roughly mark the boundary between W.Va. and Va. On the south

and east…the state’s 1170-mile boundary, which for the most part follows the course of rivers or the line of

mountain ranges”

Richard W. Stephenson and Marianne M. McKee, ed., Virginia In Maps: Four Centuries of Settlement,

Growth and Development (Richmond, Library of Virginia, 2000). page 83. Most historical atlases of U.S. history give insight

into the partition border of 1863. Peter Jefferson’s map series and its derivatives show how little was known about

the grounds west of the Warrior’s Road. A few colonial era maps exist and require interpretation, for example, West

Virginia is called Florida, West Augusta, Kanawha, Transylvania, Westylvania, Vandalia and Franklin in various proposed jurisdictional

maps. The most common phrase inked onto the transmontagne Virginia region is probably “Reserved for the Indians.”

Map II-21-A-D: Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson, “A Map of the most Inhabited part of Virginia…drawn by Joshua

Fry and Peter Jefferson [Albemarle County Surveyor and Deputy Surveyor] in 1751.” Also page 82, Map II-20 “A General

Map of the Middle British Colonies in America (Philadelphia) 1755” a.k.a. the Lewis Evans map.

Richard von

Glahn, The Son Yuan Ming Transition in Chinese History (Cambridge: Harvard U. Press, 2003), page 48: “The Annales school

privileged economic and demographic movements over politics and ideas as the defining forces of historical change, and this

shift in historical understanding entailed a reconceptualization of historical time. Slow ecological permutations, secular

economic/demographic cycles and lastly the history of events”

Gail Roberts, Atlas of Discovery (New York:

Crown, 1973) page 77, Richard W. Stephenson and Marianne M. McKee. Virginia In Maps: Four Centuries of Settlement, Growth

and Development. Richmond: Library of Virginia, 2000.also see Encyclopedia Britannica’s “West Virginia.”

Writer’s Program WPA West Virginia page 45 records these facts. The National Road, Cumberland to Wheeling completed

1818. First functional and first commercial steamboats on the Ohio River, 1811, 1817. Staunton to Parkersburg Road 1823-1847.

Northwestern [Virginia] Turnpike incorporated 1827. Winchester to Parkersburg Road 1838. Baltimore and Ohio Railroad started

1827 reaches Ohio River 1852. “Eastern Virginia interests fought with all their power in the General Assembly to impede

its [B&O RR] progress.”

James Holmberg, ed. Dear Brother: Letters of William Clark to Jonathan Clark.

(New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002). Page 200.

Twohig, Dorothy, ed. Letters of George Washington, Retirement

Series. (Charlottesville:UVA Press, 1998) Volume one page 453, letter from Washington to Daniel McCarty November 3, 1979.

WPA, West Virginia page 100, John McCardell The Idea of a Southern Nation: Southern Nationalists and Southern Nationalism

1830-1860 (NewYork: W.W. Norton, 1979). McCardell examines the fault lines of the old Virginia trans-Allegheny political relation

and gives unusual emphasis to the 1829-1830 Virginia Constitutional struggle, and the second convention of 1850 and views

these as preliminary to Southern Nationalism, Virginia’s secession and West Virginia’s counter-secession.

Shaffer, Clash of Loyalties, Introduction

Writer’s Program WPA West Virginia, page 51, “The B and

O Railroad was subjected to attack continuously. The RR officials tried to maintain a neutral position, thus they changed

their tactics after Jackson had corralled a large portion of their rolling stock and run it into the Shenandoah [Valley] their

support was thrown to the North and made itself felt in the formation of W.Va. and the later inclusion of the Eastern Panhandle

counties in the new state.” See also Daniel Crofts, Reluctant Confederates: Upper South Unionists in the Secession Crisis

(Chapel Hill: UNC 1989) on the border areas significance.

Otis Rice, West Virginia, page 147-151.

Shaffer,

Clash of Loyalties, Appendix Charts.

Fernand Braudel, The Mediterranean. ...........................................................

BIBLIOGRAPHY By David Shanet Clark

|

|

|

|

|